A stunning museum has recently been opened adjacent to the Royal Palace in Madrid. The…

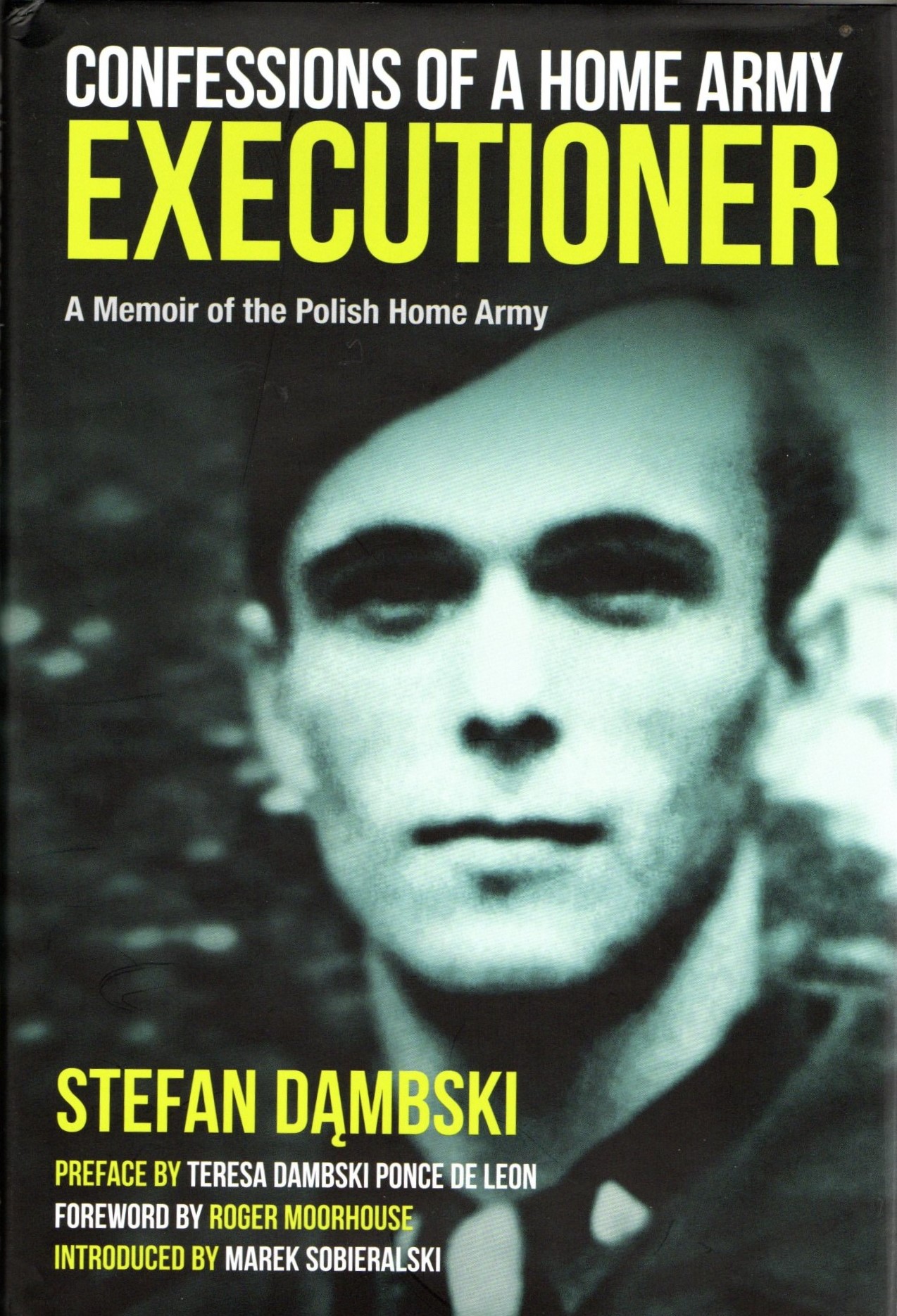

Confessions of a Home Army Executioner

Stefan Dąmbski was a Polish Home Army veteran. More importantly, he was one of their wartime executioners briefed with the task of eliminating both Nazi enemies and Polish collaborators. His memoir has now been translated into English by Marek Sobieralski and Jonathan was asked to contribute the following review, published in the hardback volume by Greenhill Books.

This is a harrowing but important book. Written by Polish Home Army veteran Stefan Dąmbski and now excellently translated into English by Marek Sobieralski, this memoir records a rapid journey from a fresh-faced teenager into a seasoned executioner. This is also a moral tale of how war can corrupt and how even justified resistance can produce moral dilemmas.

The Polish Underground was a formidable organisation and was the largest resistance movement in occupied Europe. Unique in that it comprised both a military wing, Armia Krajowa or Home Army, as well as a civilian support network that filled the educational and social welfare void resulting from the Nazi occupation. During this occupation, Home Army courts passed death sentences on a variety of particularly unpleasant SS or Wehrmacht soldiers and functionaries. More controversially, similar sentences were passed on a number of Polish-born and Volksdeutsche civilians who had collaborated with the enemy. Although the vast majority of Poles resisted the Nazis in any way they could, enemy occupations always throw up opportunists who can turn on their neighbours for a bribe or wish to settle old scores. Dąmbski was one of the few AK members who volunteered to carry out these death sentences and therefore his memoir provides a rare chance to examine the mind of an ‘executioner’.

This is not an easy read – the slaughter of both men and women is unremitting. And when the Nazis retreat before the end of the war, the Poles are forced to endure another occupation, this time by the Soviet Red Army. The executioner’s skills are called for again, and Dąmbski willingly obliges.

In later life, Dąmbski blamed his role as executioner on his fervent adherence to his motherland. He claims that a deprived childhood and the pre-war climate of Polish nationalism prompted him to carry out his role with such zeal. Yet the reader is left with the feeling that the more targets he killed, the less sensitised he became and indeed, at times, he relishes his role. In the end, dispatching men and women who were deemed enemies of the cause becomes routine. In later life he made a confession, of sorts, for the brutality he had meted out during the war, and when he received a terminal cancer diagnosis in 1993, he killed himself, perhaps in the same calculating way.

Such is the secret nature of clandestine warfare that most of the incidents he describes cannot be corroborated. However, few would willingly boast of such bloody excesses and Dąmbski

has left us with an unusual and extraordinary testimony of what enemy occupation can do to a people. Indeed, in occupied territories across the world today, his role is far from redundant.

Jonathan Walker

This Post Has 0 Comments